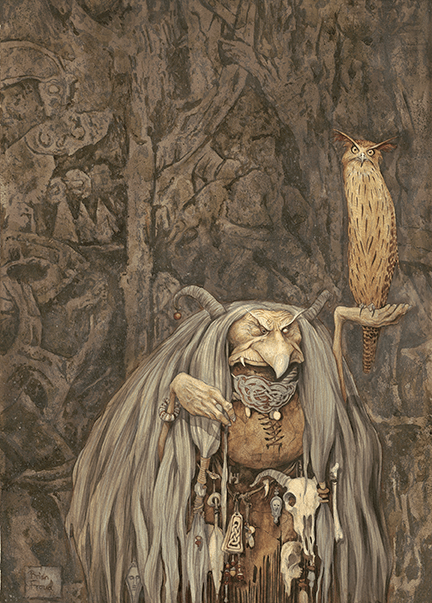

Image credit: MYSTIC – BRIAN FROUD, ACRYLIC AND COLOURED PENCIL. DARK CRYSTAL GRAPHIC NOVEL

To discuss the art of Brian and Wendy Froud we must first cross into the Faerie Realm, so let’s begin with Brian’s advice on where that enchanted place can be found: “Faeries,” says Brian, “exist ‘betwixt and between,’ inhabiting transitional spaces: in the liminal space at the edge of the woods; in the dusky light between night and day; in the imaginative place where our rational mind balances with the fluid irrational.”

As artists, the Frouds are just as fluid and mutable as the faeries, working in the borderlands between a range of disciplines and genres: creating paintings, drawings, sculptures, dolls, puppets; and concept designs for book publication, exhibition, film, television and stage. What unites this work is an aesthetic vision, a “Froudian” style first developed by Brian as a young artist in the 1970s, and expanded in collaboration with Wendy over many years of creative partnership.

Brian was born in Winchester in 1947, raised in rural Kent, and studied at the Maidstone College of Art, where his childhood love of myth was rekindled by a book of Arthur Rackham illustrations found in his college library. After five years working as a commercial illustrator in London, Brian moved to a remote Dartmoor village where he shared a house with fellow-artist Alan Lee and his family. Inspired by the wild landscape around them, the two friends collaborated on Faeries, an illustrated book of British faery lore published in 1978. This ground-breaking volume quickly became an international bestseller and has influenced artists, writers and folklorists all around the world in the decades since. Brian’s magical vision so impressed American puppeteer and filmmaker Jim Henson that he asked Brian to come to New York to design two feature films: The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth. It was on the set of The Dark Crystal that Brian met Wendy, who created the “gelflings” and other creatures for the film.

Wendy was born in 1954 in Detroit, Michigan, where her parents were artists and teachers at the Art School of the Society of Arts and Crafts. “I grew up sort of living in the art school,” she says, “and started making dolls around the age of five, as soon as I could bend a pipe-cleaner and bits of fabric together.” After training in ceramics at the Center for Creative Studies, she moved to New York and landed a job in Jim Henson’s Creature Shop, making puppets for The Muppet Show, The Muppet Movie, and fabricating Yoda for The Empire Strikes Back. She met and married Brian during the filming of The Dark Crystal. Their son Toby was born before filming on Labyrinth began, and he appeared in the film as the baby stolen away by David Bowie’s Goblin King.

After Labyrinth, the Frouds settled back on Dartmoor, rooting themself in a timeless landscape that still held a living faery tradition. Although they continued to produce designs and puppets for the screen (most recently for the Netflix television series The Dark Crystal: The Age of Resistance), they chose to give the bulk of their time to more intimate work: portraying their vision of the magic shimmering in the leafy green world around them. While Brian painted faeries, goblins and trolls, Wendy brought these same creatures to life in three-dimensional form. This work resulted in a long roster of books, including Brian Froud’s World of Faerie, The Art of Wendy Froud, Good Faeries/Bad Faeries, A Midsummer Night’s Faery Tale, Goblins, Trolls, Faeries’ Tales and the hilarious Cottington series of “pressed fairy” volumes. Brian is always quick to note that he is not an illustrator in the traditional sense of working from an author’s text. In these volumes, the artwork always came first; the text was then written to elucidate the image, not the other way around. Terry Jones (of Monty Python fame) was one of the writers who worked with the Frouds in this manner (Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book, 1994), and I was another (the “Old Oak Wood” series, 1999-2003). More recently Wendy has taken this role herself, for who could be better at teasing out the stories that lie at the heart of her husband’s paintings?

Although the Froudian art style begins with Brian and his life-long exploration of the Faerie Realm, it’s not quite right to say that Wendy’s contribution to the “World of Froud” merely echoes his. Rather, her art is in dialogue with Brian’s, and the two are in constant creative communication. Though they work in different mediums, and labor in separate studios, they keep coming together to show and discuss and argue and laugh, poking and prodding the best out of each other. It’s such a fluid process that even I, who have worked with both, cannot tell where the line between them is drawn. They seem to share a muse who lives, like the faeries, betwixt and between.

And yet those separate studios are important too. Brian’s workspace, on the ground floor of their 17th century Devon longhouse, is a strictly private place. (I’ve seen it only once in all of the years I’ve known him.) His working method is intuitive, fluid and metaphysical, but also exacting:

I start each painting by drawing a geometrical grid based on the Golden Section, a system of proportions and perspective developed by the ancient Greeks. The grid is overlaid with circles, triangles and the like, and where these things cross over is where I place the major figures. This gives the “chaos” of a crowded painting an underlying structure of order. The central human figure is generally based on a photograph—this provides an underpinning of reality for the more fantastical aspects. I take my own photographs of models: friends and neighbors generally. The imagery surrounding the central figure is always in relationship to it. I prefer to keep my rendering as loose as possible, just on the edge of being finished. I want a painting to give just enough information for the picture to make sense; there should always be a little bit kept back, a few pieces missing, which the viewer must supply himself. In doing that, the picture comes to life. It becomes part of a reciprocal process, a communication. The painting allows you inside, where it can grow, and you can grow.

Wendy’s studio, in the eaves of the house, is a room filled with sculpting materials and tools, fabrics and feathers, stones and bones and fairy tale books and old photographs—plus dolls, sculptures and puppets in various stages of construction. Wendy also views art-making as a magical act, a means of summoning the numinous spirit of the natural world—grounded by a thorough knowledge of her craft gained through her upbringing, art school training, and years in the Henson workshop. Laboring on the set of The Dark Crystal was, she says, a crash course in learning how to employ a wide range of materials and techniques, and to work quickly and confidently to deadline. (For a recent project, she set herself the challenge to work more slowly to see what a more leisurely pace might bring to her creative process.) Her film work has also given her an ease with creative collaboration that serves her well in working with Brian. After all these years together, she still marvels at the art he produces and the ways that it sparks her own. She says,

Ultimately, Brian and I take our inspiration from the same place: the archetypal Cauldron of Story, full of all the myths, faery-tales and magical stories told and retold through the centuries. And of course, we’re both nurtured every day by the deep quality of enchantment in the place where we live. The ancient stone circles, the Bronze Age hut circles, the medieval churches and bridges, the wildflowers of the hedgerows and the fungi of the woods: it’s all part of daily life on Dartmoor, and it’s all part of the art we create.

As Brian puts it:

After a life-time of painting and sculpting faeries, Wendy and I are often asked if we “believe” in them. The best answer I can give is that I don’t have much of a choice of whether I believe in them or not: I work by intuition, and faeries keep appearing on the page before me. Mind you, it’s not that I lie around on a chaise lounge waiting for inspiration to strike—painting is a discipline and I’m in my studio working a regular work day from 9 to 5. But on a Monday morning I’m often not sure what exactly I’m going to be doing next. I’ll get out my tools, I’ll get to work, and something will demand to come through—some creature will form on the page before me, demanding to say: Hello!

Terri Windling

Writer, editor, folklorist

Winner of the Mythopoetic Award and 10 World Fantasy Awards, including the Lifetime Achievement Award