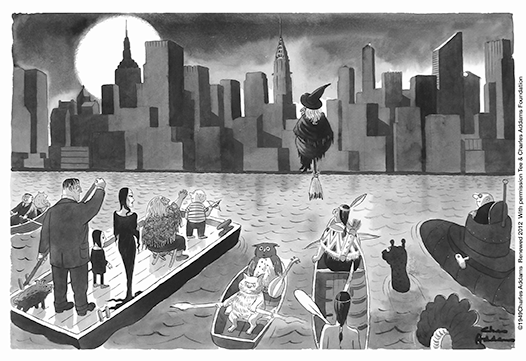

Image credit: Boats to NYC, The New York Times. Pen, ink, wash

Although time and age had no bearing on his demeanor, Charles Samuel Addams would have turned 110 in 2022. In that same sense, he would be humbly surprised that his contribution to the world of cartoon art is as profoundly alive today as it was when it was first published in The New Yorker magazine in 1933.

Critics of his work during those early decades often suggested his cartoons were menacing, even deviously frightening, while by today’s standards that same body of work is considered brilliantly dark and uniquely off-center. The variety of subject matter increased as he honed his craft, from art and architecture to creatures and fairy tales, from history and military to his beloved Manhattan, and his largest body of work, one that was devoted to relationships. Political and contemporary topics rarely appear as themes because he felt that such observations only lasted as long as the daily newsprint on which they were published.

Addams was in awe of machinery and all forms of transportation when he was a young child in his hometown of Westfield, New Jersey. Through the encouragement of his mother and maternal aunt, who accompanied him to watch the passenger and freight trains at nearby stations, he drew everything he saw. With the advent of the First World War and the years following the war’s end, Addams was precociously adept at creating cartoons of Kaiser Wilhelm and soldiers and artillery and battles. It should come as no surprise that as an adult he became a collector of ancient weaponry and suits of armor, incorporating them into his work devoted to castles, knights and early warfare.

The phantasmagorical illustrations created from wood carvings, and engravings by 19th century French artist Gustave Doré caught Charlie’s attention at a young age. Perhaps what contributed most to Addams’s childhood education was the atmospheric and darkly moody work found in Doré’s illustrations in the oversized 1883 edition of The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe. During his lifetime, Addams penned as many as a dozen cartoons devoted to Poe, and the writer’s eventual selection of a raven to utter that prophetic word, “Nevermore.” One of Addams’s versions has a contemplative Poe seated at his desk with nine ravens offering suggestions such as, “Carnivore,” “Shut the door,” and “Blood and gore.”

Though Doré occupied his childhood fascination, Addams later discovered and embraced the work of Arthur Rackham, England’s leading book illustrator of the early 20th century. Charlie’s work certainly reflected the influence of Rackham’s hauntingly detailed, pen-and-ink scenes of twisted and gnarled trees and nubby creatures, complete with a plethora of witches and gnomes bearing devious grins.

As a maturing artist, Charles Addams became more painterly, with great attention to skies and clouds and atmosphere, not unlike Albert Pinkham Ryder, a late 19th century American painter he greatly admired. Ryder’s use of dark colors and swirling heavens and tumultuous seas were elements Addams would incorporate in the backgrounds of his otherwise humorous vignettes.

These influential talents may have a bearing on Addams’s love of the darker side of his technique, but he was his own artist with his own style, which had begun as India-ink line drawing, soon to be enriched by a fuller palette. Known primarily as a cartoonist working en grisaille, it should be noted that he also worked very comfortably in full color, having produced 65 color covers for The New Yorker alone. The near-weekly publication of his wicked cartoons in that magazine and in newspapers, such as those in the McClure Syndicate, made him a household name. This level of popularity opened up an entirely new avenue of work in the world of print advertising. Addams helped to sell products as diverse as Suntory Scotch and Angelique perfume and Polaroid cameras, and even Volkswagens. He was still producing commercial work upon his passing in 1988.

Thanks in part to his father’s early career as a naval architect, Charlie seemingly inherited a level of draftsmanship that would translate into his precise architectural drawings, another unique element of the Addams cartoon. He spent endless hours reworking a drawing until the details accurately represented the theme. Dona Guimares, one of his closest female pals, was the editor of the Home Design and Entertaining sections of The New York Times. With access to the paper’s vast architectural and furniture files, she often gave him copies for his own reference work, while the world of museums, cemeteries and city edifices were his playground and his homework.

Charlie was a polite, soft-spoken man with a wicked sense of humor, as is evident in much of his impressively large output. He bore a passing resemblance to his good friend Walter Matthau. His boyish demeanor was welcomed in all social circles, and he travelled comfortably with the upper crust. He had a great list of male friends, from the elites listed in the Social Register, to his fellow artists and auto racetrack buddies and vintage car tinkerers. But his love of women seemed to rule his life. He loved showgirls, artsy women, classy “dames,” both married or single, city girls and country girls alike, with a secondary fascination for redheads.

His first marriage was to a fellow Westfield resident, Barbara Day, whom he later referred to as “Good Barbara.” It was a bit of a rebound relationship, because his first choice came from a well-heeled Westfield family whose lawyer advised them against their daughter marrying a man who was simply a cartoonist. After their break-up, she eventually rebounded with a man who himself became a cartoonist, though not as highly acclaimed as Addams. Day and Addams parted after it became clear that her desire was to have children, while his was not. Then, in the early fifties, along came Barbara Estelle Barb, whom Charlie nicknamed “Bad Barbara.” She would supply him with most of the treachery he imbued in the cartoon subject he mined most frequently, that of relationships. She used Addams’s naïveté to gain the attention of a pliable English lord, who became her second husband, all the while tormenting Addams by tearing up his artwork, cutting off the sleeves of his suit jackets and destroying all evidence of prior paramours. From courting, to marriage, to the plans on how to end it all and what to do with the body, Addams drew images from the viewpoint of both the husband and the wife. During their eighteen-month marriage, Bad Barbara had a strong influence on his artwork of the time.

He took a thirty-year break from marriage and happily enjoyed the company of many women, including Jacqueline Kennedy, Joan Fontaine and even Greta Garbo, to name his more well-known partners. In 1980, he agreed to wed his longtime friend and lover, Marilyn “Tee” Matthews, both of whom having vowed to never marry again. It is this wife who strived to preserve the Addams oeuvre by forming the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation.

Finally, there is The Addams Family, a name that Charlie himself was loathe to agree to with the television producers. His Family was represented in 80 published cartoons scattered throughout his work from the 1930s to the 1980s, amid the thousands he produced using other subjects and in other genres. He owned a twelve-inch RCA Victor television that made a buzzing background filler, clearly confirming that television was not his milieu. He was amused that Hollywood came to his door, but a bit disappointed when what he’d intended for the characters (which would become known as The Family) were treated as laugh-track comedy. His ideas for the Family actually represented little difference from “the norm” of the day. They just lived on the dark side of the mirror. His objective was to suggest that we stop judging the book by its cover, that characters such as his were equally valid in their efforts to survive and raise a family. There was never a drop of blood in any of his work, though mayhem was always evident and torture was applauded with love, a dichotomy he found universally evident .

Regardless, the entire Addams oeuvre still supplies the public with its comedic darkness, both in print and in all the other forms of media it fosters. His contribution to the art world is clearly timeless.

H. Kevin Miserocchi, TrusteeT

Tee and Charles Addams Foundation