Image credit: New York Times

On June 28, 1926, George Booth entered the world, surprised and a little confused, on top of his grandmother’s kitchen table in Cainsville, Missouri. He was the middle child of a school superintendent and a school teacher in the small farming community. At the tender age of three he started drawing “racer cars stuck in the mud,” which amused both him and his mother, who let him stay up past his bedtime to draw with her. His father offered to let him have as much paper as he wanted—as long as he “didn’t waste it,” since it was during the Great Depression when supplies were scarce—because he saw in his son a deep passion he knew should be nurtured. George kept drawing, and he studied art under the tutelage of his mother, Maw Maw Booth, who was an artist in her own right. When his father felt his son needed a more reliable career to fall back on, he got him a job as a printer’s devil at Sim’s Print Shop, which put out the local paper. George worked there, for 40 hours a week at 25¢ an hour, while he was in high school, from the age of 16 until he was 18 and drafted into the Marine Corps during World War II.

When asked by the recruiter what he wanted to do in the military, George said he wanted to draw cartoons. The utterly astonished recruiter, by the name of Harry K. Bottom, wrote it down, but told him that he could draw a bead on the enemy instead, so George spent the war in the Pacific training for a huge invasion of Japan which never transpired. Instead, the Bomb was dropped. After the war with Japan ended, George remained on Maui, in Hawaii (not yet a state), to help with the cleanup effort.

One of George’s duties was to clean the 12-holer latrine. He was given a can of petrol and a box of matches and told to add a squirt into each hole, then throw in a match for sanitation by fire. Now, liking to do a thorough job, George gave a good squirt on all the “nassness” in each hole, using much more than a single squirt to make sure it would be sanitized. Then he lit the match. The building blew up. A 20-foot column of smoke and fire brought the remaining Marines in the area to come and watch the 12-joker burn down. Questions were asked, which led to the higher ups finding out who was responsible. George would have been sent to the brig had it not been recently sawed off at its supports and disposed of. Instead, he was sent to an Eden-like ravine with a stunning waterfall where he had to pick up trash all day, allowed up only for meals and to sleep.

When George was readying to leave the military, he received a telegram inviting him to come work as a cartoonist and staff artist at the Marine Corps’ Leatherneck magazine in Washington, DC. He was euphoric until he received the second telegram, which contained the caveat that his employment hinged upon the fact that he re-enlist. So he re-enlisted. This was to the shock of the other Marines, who once again came from all over camp, this time just to take a look at the idiot who re-enlisted after the nightmare in the Pacific. Despite being recalled for the Korean War in 1950, George’s seven years in the Marine Corps provided him with much, including an auspicious start to his cartooning career with his work at Leatherneck, countless stories, and friends who he has remained in touch with into his 90s. Not to mention the G.I. Bill, which allowed him to attend art school at the Chicago Academy of Art, the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, DC, and the School of Visual Arts and Adelphi University in New York.

During the time between wars, George took up judo in Chicago with Japanese instructors who had just come out of internment camps in the US. It created a lifelong love of the sport and a deep appreciation of the Japanese people, their culture and design sense. He continued to play judo into his early 70s and achieved the rank of Black Belt, which he received from the Kodokan Judo Institute in Japan. His friend Dr. Masayori Inouye picked it up for him on a trip back to Japan in the 1980s. During that decade, George and his friend, a distinguished biochemist, were part of a lively group who practiced judo together.

After the Marine Corps and art school, George moved to New York City to pursue cartooning. He attacked freelancing by making the rounds to all the major publications at the time, which included The Saturday Evening Post, Playboy, Collier’s, King Features, The New York Post and The New Yorker, to name a few. While selling his work to most of these markets, it wasn’t until much later that made his first sale to The New Yorker, which truly launched his career.

While freelancing in the 1950s he met and managed to marry his wife Dione, to whom he is still married. When riding all over Manhattan and the western end of Long Island with George in his Model T, Dione thought he was “rich and eccentric, only to find out he was just poor and weird,” but by then it was too late and there was no turning back. Now with a wife and plans for a family, George wanted a more reliable paycheck. Hired by Morgan Brown at Bill Communications, he served as art director for several trade publications, including Modern Tire and Plastics Technology. Morgan, his immediate boss, became a good friend, and George would often hang out in his office and watch him deal with various and sundry people who came in with one problem or another. After they’d plead their case or make their excuses, Morgan would say, “Life is hard and DAMNED unfair.” This would make the person feel that things were somehow resolved and they’d go merrily on their way. Over the years, George would often quote Morgan, and in his own household no one was allowed to say things weren’t fair.

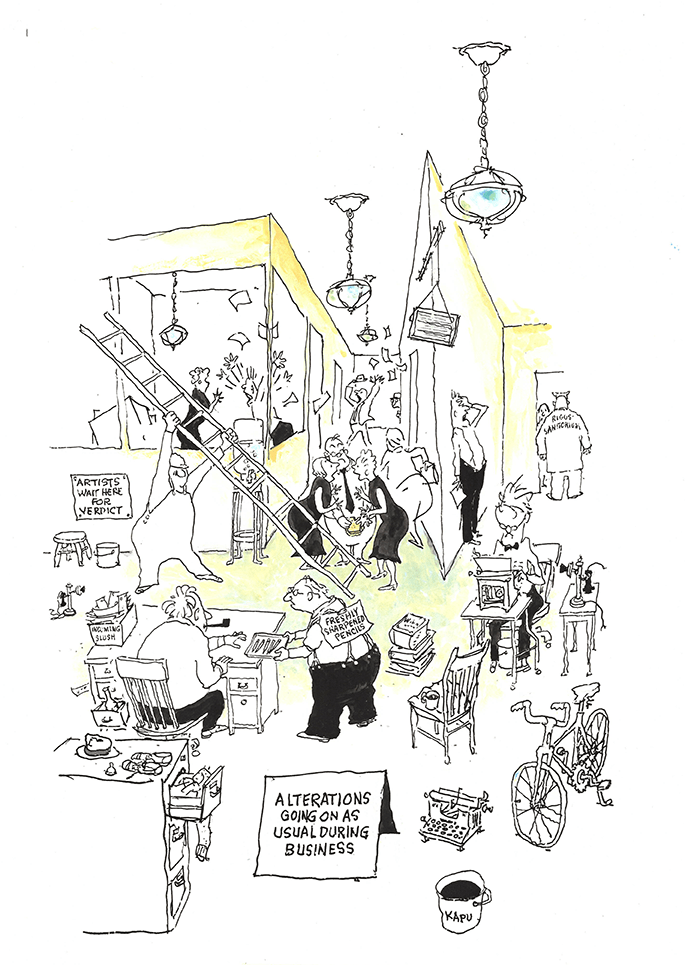

In addition to doing layout and design, illustration and cartoons, George had the difficult task of hiring and firing. He had a trick up his sleeve though. His Leatherneck buddy, Ken Hine, an art director at Reader’s Digest, would send George wonderful candidates that Ken had been unable to hire himself. By hiring a great staff, George could do a little more illustration and cartoons for the publications. But as the years passed, it wasn’t enough, and the long workdays made it a challenge to do batches of cartoons for the freelance market, since he could work on his own material only on weekends. At one point, George discovered that what he earned as an art director didn’t come close to competing salaries in the field. He asked for a raise, one that still didn’t approach the going rate, but one that would at least allow him to live a bit above the poverty line. He was told there wasn’t room in the budget and that everyone else would want a raise. Nearing his late 30s, George decided this was just unacceptable and he quit. When he headed outside, a magazine cover on a nearby newsstand caught his eye. On it was a big article about men his age who had had midlife crises and had quit their jobs.

The return to full-time freelancing turned out to be an excellent move and much more satisfying.

The late 1960s brought changes in the cartoon market, and just as George was to get a full-page spread in The Saturday Evening Post the magazine folded. However, a letter of introduction was sent to the editors at The New Yorker, and George and Charles Barsotti, The Post’s former cartoon editor, began their long and illustrious careers there.

In addition to The New Yorker and some advertising, George began illustrating children’s books starting with Wacky Wednesday in collaboration with Dr. Seuss. Seuss wrote the story under the name Theo. LeSieg, and the book is still be published nearly 50 years later.

In the mid-1990s an illustrator, also by the name of George Booth, passed away and was mourned by his friends at the Society of Illustrators in a tribute in The New York Times. Cartoonist George Booth’s worked suddenly dropped off, and his wife was getting calls and cards of condolence. So he made a call to the Times asking them to print a retraction to clarify the fact that it was the illustrator who had passed away, but that the cartoonist was alive and well and still working to support his family.

George’s long career, over 50 years alone at The New Yorker, brought him not only a living and treasured friendships, but a honorary doctorate from SUNY Stony Brook, the National Cartoonist Society’s Milton Caniff Award, and the great satisfaction of bringing laughter and a break from life’s stresses to his fans.

At 93 George’s health pushed him towards retirement. He continues to visit with his long time cartooning friends, and to live and breathe humor.

Sarah Booth

Artist’s daughter, Production Artist, The New York Times