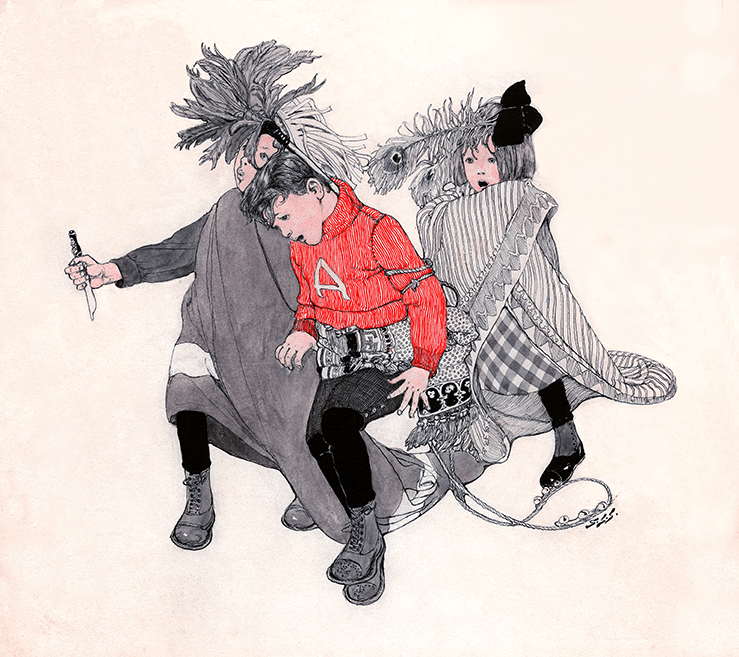

Image credit: Sarah S. Stilwell c.1906, The Eisenstat Collection, courtesy of Alice A. Carter and J. Courtney Granner

In 1909, a New York newspaper proclaimed that Sarah S. Stilwell Weber ranked “high among the illustrators of this country.” She was also amongst the highest paid. The article observed that illustration was a career open to women, and “a present-day girl of artistic tendencies has 100 opportunities for expression and success….”

But it wasn’t that easy. A mere ten years earlier, Sarah was a student at Howard Pyle’s legendary school for illustrators. Pyle accepted women in his class but criticized “those damned women…who placidly knit while I try to strike sparks from an imagination they don’t have.” Pyle insisted that any woman who hoped to become an illustrator should give up all thoughts of marriage, because when a woman married “that was the end of her.” He warned Sarah that if she married, she couldn’t hope to keep up with the deadlines and high standards of illustration.

Ten years later Pyle’s former student was painting covers for The Saturday Evening Post, which Norman Rockwell called the “greatest show window in America for an illustrator.” At the same time she was happily married with a baby daughter. In an era before women had the right to vote she was earning more than a Supreme Court Justice.

To accomplish this feat, Weber not only had to deal with the challenges confronting every beginning artist, she also had to reject the advice of her beloved mentor and navigate a path through assumptions and prejudices about women illustrators. She also had to adapt to an era of revolutionary change in publishing, as the modern magazine was being invented. During her lifetime, the technology for reproducing illustrations changed from black-and-white wood engraving to full-color photomechanical images. Pyle urged his students to train for a future when full-color reproduction would be possible. Weber did, and a career which began with black-and-white line work, progressed through two-color covers for the Post, and ended with full-color oil paintings.

Sarah Stilwell Weber was born in 1878 in Concordville, Pennsylvania, the youngest daughter of William Stilwell, a harness maker, and his wife Isabella. Sarah loved to draw and took her first art classes at age 17 at the Drexel Institute. Concordville turned out to be just three miles from Howard Pyle’s school for illustrators, where she continued her art training. She sold her first illustration to Collier’s Weekly in 1898, and that same year illustrated her first book, Dorothy Dean: A Children’s Story by Ellen Olney Kirk. Her black-and-white drawings of children at play helped to earn her a full scholarship with Pyle. She studied with him until 1900, then set up a studio to work in Delaware, close to her mentor.

After graduation, Weber received a steady stream of small assignments from publishers, gradually progressing from spot illustrations in line to full-page half tones. In 1902, she illustrated a poem called “Christmas Hymn of Children” for Century Magazine. In 1903 she completed a pictorial essay for St. Nicholas with half a dozen drawings of children on the theme of “Happy Days.” The drawings were well received, and in 1904 her career took off. She painted a distinctive cover for the New Year’s issue of The Saturday Evening Post in a decorative, Art Nouveau style, and before long she was creating covers for Country Gentleman, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Collier’s and St Nicholas.

Many of these covers depicted strong, stylish, sophisticated women. For example, her March, 1906 cover for Collier’s Monthly Magazine shows an exotically dressed woman lounging with two wild leopards which she has apparently ensorcelled. One of the beasts lies resting with its giant head in her lap.

Weber’s covers for the Post became so popular that its editor in chief, George Horace Lorimer, offered her a contract with a regular slot on the cover. This was the same role later given to J.C. Leyendecker and Norman Rockwell, but Weber turned it down. She wasn’t sure she could deliver on a fixed schedule the kind of work she wanted to do. However, over the course of her career she did paint 60 covers for the Post.

Weber, now an established professional illustrator, moved to Philadelphia and was welcomed into the ranks of the Plastic Club, an arts club for women. The club had been established by older graduates of Pyle’s school, such as Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green and Violet Oakley. But, unlike her peers, who had taken Pyle’s admonition seriously and pledged not to marry, when Herbert Weber, an English teacher, “wooed her with Chopin nocturnes” in 1908, she married him. The couple had daughter Jane in 1909.

Weber was already well known for her child-oriented pictures, but many felt that with the birth of her daughter her work deepened and matured. Jane became a model for many illustrations, including several Post covers. In 1913, Weber illustrated a series of “famous playgrounds” for Scribner’s, but instead of the fairylands and dreamscapes that were the setting for many of her illustrations, she placed her children exploring and at play in more urban and realistic scenes, such as Central Park, with cars and tall buildings in the backgrounds, and “Keep Off” signs gently intruding on the child’s fantasy world. It was clear that pictures of children would become her primary focus, and the centerpiece of her legacy. Commentator Meredith Eliassen wrote:

Sarah’s work after her mentor Pyle’s passing, when accompanied by her own poetry, prose, and music, creates a feminine view of childhood that blends the subconscious dream lives of children with active play lives. Her compositions of children playing and children reflecting in natural settings often included ordinary places like backyards, shorelines, and meadows of flowers. She delineated the subconscious dream lives of children along with their active play lives to illustrate how children naturally used objects including dolls, toys, and books to work through issues of growing up. She utilized the three elements coming from the Art Nouveau movement: symbolism, naturalism, and decorative ornamentation.

In addition to her magazine covers, Weber illustrated books and magazine articles. Her books included the Rhymes and Jingle series, First Reader: Child Classics, Mother’s Hero and The Luxury of Children and Some other Luxuries. In 1925 she created her last major book, titled The Musical Tree. Her husband Herbert wrote the story and Sarah drew the illustrations. The book was ambitious and appeared to be something of a summation. As one critic later wrote, “The Musical Tree shows how Sarah’s career unfolded: she was able to synthesize elements of childhood utilizing all of the experience and illustrative styles that converged through her twenty-five year career.”

She also illustrated advertisements for Kiddie Kar toys, Rit Dyes, Scranton Lace Company, and Wamsutta Mills. Her series of ads for Kiddie Kar were republished in a small book called Kiddie Kar Verses.

Weber created her last cover for the Post in 1921, and after completing The Musical Tree in 1925, she chose to spend more and more of her time quietly with her family. She passed away at her home in Philadelphia in 1939.

David Aperitif

Art critic for the Saturday Evening Post

Author, The Life and Art of Bernie Fuchs, The Life and Art of Mead Schaeffer, Robert Fawcett: The Illustrator’s Illustrator, Austin Briggs: The Consummate Illustrator, State of the Art: Illustration 100 Years After Howard Pyle