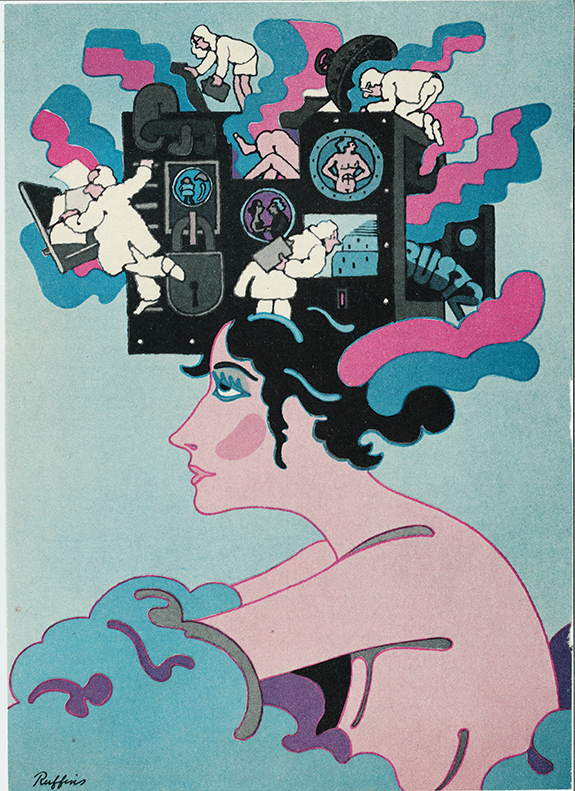

Image credit: “How to improve your memory”, Cosmopolitan, September 1975.

New York City native Reynold Dash Ruffins was born in Queens in 1930. He attended the High School of Music and Art on the Upper West Side where he befriended Milton Glaser. The classmates went downtown to attend the highly-selective, tuition-free Cooper Union. Ruffins graduated in 1951, and 21 years later he was presented with The Cooper Union Presidential Citation for prominence in his profession. Then, in 1993, he received the institution’s prestigious Augustus Saint-Gaudens Award for outstanding professional achievement in the arts, a high honor indeed. But it was as a Cooper undergraduate that he formed the relationships that would determine much of his life in the graphic arts. And, it was at Cooper that he met Joan Young, his future wife.

During one summer break, Ruffins, Glaser and classmate Seymour Chwast formed Design Plus, a firm that serviced its clients—there were two—before classes resumed. Then, while Glaser was in Italy on a Fulbright scholarship, Ruffins, Chwast and Ed Sorel, another classmate, created a parody of the Farmer’s Almanac called the Push Pin Almanack, for which Ruffins designed the logo. It was a snappy, ephemera-rich promotional piece in a coy, neo-vintage style, intended to drum up work from art directors.

In 1954 Ruffins married Young, who was asked to leave Cooper when she got pregnant! After the couple had a son, Ruffins opted for the job security as a staff member at William Douglas McAdams, the pharmaceutical ad agency, over the offer by Cooper buddies Glaser, Chwast and Sorel to join their newly formed Push Pin Studios. Once the studio had secured a sufficient roster of clients, Ruffins joined them. As described by Penelope Green in The New York Times, “In witty, faux-nostalgic drawings and lettering [the partners], all illustrators, turned the field on its head. In so doing they largely created the postmodern discipline of graphic design, by taking what had been disparate roles—illustration and type design—and putting them together.” She quotes graphic design historian Steven Heller, the editor of The Push Pin Graphic: A Quarter Century of Innovative Design and Illustration, “They did it by using vernacular forms like cartoons, and by going back into styles like Art Nouveau and Art Deco and reinterpreting them. . . . They brought pastiche into the vocabulary of design and made it cool.”

The team solved a wide range of graphic solutions that included book jackets, editorial illustration, record covers and posters, many of which became icons of the era. Ruffins stayed at Push Pin for five years, then went out on his own in 1960.

One of the first African American graphic artists to achieve prominence in the pre-Civil Rights movement, Ruffins surprised some clients when he showed up to their whites-only offices. In one instance, author Jane Sarnoff, his longtime book collaborator, recalls, “Reynold had a rush job from a major agency. Instead of sending it by messenger he took it down himself, only to be told to use the service entrance. He took the package back to the studio, called the art director to have the art picked up.” Ruffins himself had said of the incident, “The assumption was, if you were Black, you were delivering something.” Ultimately, the acceptance of his work broke through any color lines.

In 1961, advertising executive Byron Lewis and others created The Urbanite, a magazine targeting what it called “the New Negro” with contributions from James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Langston Hughes and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka). Ruffins contributed designs to the publication and was described by Lewis as a “pioneer” who served as a role model who worked in the almost exclusively white Mad Men-era advertising world.

Ruffins teamed up with Simms Taback, yet another Cooper alum, who had also worked at McAdams, to form a successful design studio in 1963. The partnership would last 28 years. In 1989 they started Cardtricks, a greeting card company, promoting products that combined their compatible graphic style with clever playfulness.

Advertising and editorial commissions came from an impressive list of clients that included IBM, AT&T, Coca-Cola, CBS, Pfizer, The New York Times, Scribner’s, Random House, TimeLife, the US Postal Service, as well as Fortune, Gourmet and Essence magazines. Ruffins’s work was recognized by awards from The New York Art Directors Club, and a Silver Medal from the Society of Illustrators.

Throughout his career, Ruffins contributed to over 20 books, sometimes as illustrator, or, as in the case of the 13 books with Jane Sarnoff, sharing authorship equally. The diverse subjects the pair chose to collaborate on, from chess to bicycles to word origins, were driven simply by topics they found interesting. “I think Reynold particularly liked the Great Aquarium Book,” says Sarnoff, “because of the mix of his styles, from funny little spots to quite realistic imagery. He liked That’s Not Fair for the concept, which we developed together.” And, despite being highly work-intensive, he enjoyed doing their riddle books, covering topics as various as monsters, giants and space. The material from the the books was used to create riddle calendars for about 10 years.

Sarnoff remembers,“For many years Reynold worked in a jacket and often a tie, even when he was alone in the studio. Classy man.” Handsome and dapper, Ruffins’s sartorial formality belied his well-developed sense of humor that employed visual puns as well as wordplay. In one of their books, Sarnoff says, “a delivery truck in a scene is The Unique Uniform Company. Once, when I asked him to create a coat of arms, he did just that—he drew a coat made up of only arms. Another time, when I told him to “get over” something, he drew himself standing on top of the word ‘over.’

“I remember Reynold working on a pharmaceutical ad for a children’s product. The client wanted a lot of diversity in age, race, gender. The trouble was that the comp had only three children. Reynold did some quite amusing doodles of calico children (not for the client). He was a very creative doodler.”

During the days before computer art, Ruffins would patch problem areas. Sarnoff remembers that if a “client wanted a Great Dane instead of a poodle—Reynold patched it in. Wanted an apple tree instead of an oak? Patch it.” Apparently, he and partner Simms Taback had contests: the biggest, the most complicated, the dumbest client request that required patching.

The artist listened to talk radio (NPR) or classical music while he worked. When he and Sarnoff tackled a children’s book that required a lot of cooperation, she would often read short stories aloud to him when he was at the board. During their collaboration on Take Warning! A Book of Superstitions, his wife suggested The Conjure Woman, a collection of short stories by Charles W. Chesnutt, considered by some to be the most prominent African American fiction writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “We added superstitions Chesnutt had mentioned in his stories to our book,” Sarnoff says. She also read “lots of E.B. White essays, short stories, letters” by the New Yorker contributor and author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little.

In 1992 Ruffins created the illustrations for Koi and the Kola Nuts by Brian Gleeson, a critically praised video narrated by Whoopi Goldberg and scored by jazz great Herbie Hancock. Using camera pans and minimal animation of static artwork, the illustrations evoke the drama and humor of the African folk tale. The simplified, expressive images are colorfully patterned, with a Chagall-like play with perspective using stacking flat planes of color textured with shading. His animals are fanciful creatures loaded with personality. Throughout, there is a hand-made quality in the exuberance-suffused work, naïf yet graphically sophisticated.

Ruffins illustrated Misoso by Verna Aardema, which received a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly and was named one of Time magazine’s best children’s books of 1994. In 1997 he received the Coretta Scott King Award from the American Library Association for Running the Road to ABC, written by the Haitian author Denizé Lauture.

In addition to Steven Heller’s history of The Push Pin Graphic, Ruffin’s work has been featured in design publications such as 200 Years of American Illustration, A History of Graphic Design, African American Art, Graphis and How magazine. His work has been included in group exhibitions in Milan, Bologna, Tokyo and at the Louvre in Paris.

Ruffins passed on his knowledge to students at Queens College CUNY, where he held the position of Professor Emeritus. He taught at the School of Visual Arts, Parsons School of Design/The New School and was a Visiting Adjunct Professor at Syracuse University.

The Ruffinses and their four children were longtime summer residents of Sag Harbor, the Long Island community where, in 2000, the couple retired. There Ruffins would paint his exuberantly colored, “jazzy,” often abstract canvases, which he exhibited in and around Sag Harbor. In one show, “Art—a Family Affair,” he exhibited his work along with those of his late wife, who died in 2013, and their daughter Lynn Ruffins Cave. Quoted in Dan’s Paper, a local publication, he compared easel painting with the constraints of a client’s needs: “It’s only for the pleasure of design, color and line. I can do things so differently and so much more freely.”

Reynold Ruffins died in Sag Harbor in 2021 at the age of 90.

Jill Bossert

Editor, author: Mark English; John La Gatta, An Artist’s Life; Malcolm Liepke; Fred Otnes: Collage Artist