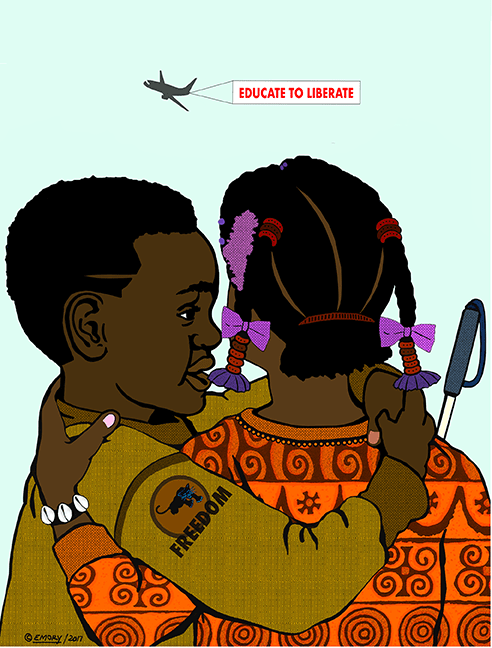

Image credit: Educate to Liberate

Emory Douglas calls himself “a manufacturer of art, of creativity.” Over his long career, others have described him as an artist, illustrator, designer and cartoonist. “Manufacturer” is the perfect word because Emory has been intensely prolific, especially between 1967 and 1982 when he was first the Revolutionary Artist, then the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (its original name).

As the primary illustrator, art director and layout artist for the Black Panther (BP) newspaper Emory created hundreds of illustrated and collaged front and back covers and interior images for the weekly tabloid-sized publication. As the BP newspaper increased its circulation to almost 140,000 copies a week in 1971, the Black Panther Party (BPP) gained popularity and notoriety. A 1970 Congressional Committee studied the newspaper and published a report with so many images by Emory and other BP illustrators that it looked like a graphic novel. Later, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover declared the BPP to be “the greatest threat to national security.”1

At the same time, in Black neighborhoods nationwide, art from the newspaper’s back covers was wheat-pasted on bare walls on the streets. People across the country removed the posters from the newspaper and hung them on their walls. Some posters were printed on heavier paper and sold individually. Mainstream press articles presented a wide range of opinions about the beret-wearing, leather-jacketed young African-American men and women who demanded, “All Power to the People!” with raised fists.

By making direct, authentic and often aggressive images, Emory and the other Black Panther artists created an unprecedented body of work in the history of American illustration.

They drew Black people with guns, visualizing self-defense against violent and passive forms of systemic oppression. In 1966, when the Black Panther Party started, it was legal to carry guns in California openly. The Panthers began armed patrols in their neighborhoods in response to police brutality that overwhelmed African American communities. These actions had two results. Police brutality temporarily became less rampant. In response, under governor Ronald Reagan, the California legislature enacted strict gun control laws after May of 1967.

In 1971 BP party leader Huey Newton officially announced an accelerating focus on survival programs that “will lead the people to a higher level of consciousness, so they will know what they must really do in their quest for freedom.”2 Emory’s previous drawings of armed citizens became motivational visual metaphors as the BP party prioritized economic issues and elected political power. Illustrations in the BP paper changed accordingly to visualize problems like the lack of housing, jobs and the poverty caused by rampant discrimination.

The Black Panther newspaper started in 1967, just three years after the Civil Rights Act passed in the US. Emory’s drawings visualized everyday Black life, countering racist images long embedded in the nation’s collective consciousness. In 2005 I wrote that Emory was “the Norman Rockwell of the ghetto, concentrating on the poor and oppressed.”3 He explained that the people in his drawings looked like someone everyone knew—aunties and uncles, grandparents, other family and community members. Drawings by Emory and the other BP artists detailed poverty’s conditions while maintaining its victims’ dignity. The artists featured everyday people who cooked dinner in roach-infested apartments and worried about how they would feed their children, in addition to portraying BPP leaders and solidarity with international liberation movements. Text around and within the drawings called out slumlords, corrupt politicians and officials, law enforcement officers, and anyone else who helped maintain Jim Crow conditions in a post-Civil Rights world.

Specific events in Emory’s life dramatically shaped his trajectory and future. He started drawing on grocery bags when he was a young boy and kept making drawings. Later, when he was a teenager, while incarcerated at a youth detention center, he was assigned to the print shop and designed a logo for the program. A probation officer later encouraged him to pursue commercial art when he declared his intention to attend community college after his release. He could have been like so many young Black males who enter the prison system as young people for minor infractions and never emerge.

Another life-changing event occurred when he was working and studying commercial and advertising art at The City College of San Francisco. He became involved in the Black Arts Movement and met Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka) at San Francisco State College. Through that group, one night he was at The Black House, which hosted cultural activities, and he met Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, leaders of the newly formed Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Later he was with them and party member Eldridge Cleaver as they laid out the first issue of their newspaper. Having learned about layout and typography, he volunteered to help them. He went home to get his supplies, but by the time he returned, they had finished and asked him to work on the next one. He worked on almost every newspaper after that.

At City College, an art instructor recommended Emory for his first paying freelance illustration job drawing chromosomes for a science instructor. He made line drawings with pen and ink on illustration board, beginning his long relationship with black-and-white drawings. He learned to use spot color while working in a silkscreen factory, where he was trained on cutting film and color separation. Other commercial art jobs introduced him to the materials and processes that helped make the Black Panther newspaper visually dynamic and efficient.

Over the years on the BP paper, Emory used his talents across disciplines, a common practice by creative people of color in a segregated world. In Black-owned and operated businesses, staff often performed any combination of design, illustration, production, pre-press or on-press work. In addition to creating most of the illustrations published in the weekly BP, he designed and laid out almost all of the issues. This is why Emory became an AIGA fellow in 2015, recognized for “his fearless and powerful use of graphic design.” Overlapping at different periods of time, other illustrators worked for the BP newspaper, including Joan Tarika Lewis, Gail “Asali” Dickson, Mark Teemer (Akinsanya Kambon), Malik Edwards and Ralph Moore. After the Black Panther newspaper ceased publication, for the next 30 years, Emory worked at the San Francisco Sun-Reporter, a Bay Area Black newspaper publisher.

Through the BP newspaper, Emory tried to move people toward liberation using images. Presenting news and communicating ideas visually to people who probably would not read the detailed articles, he accurately portrayed racism and discrimination’s impact on Black people’s daily quality of life. Visualizing Black people defending themselves against actual and metaphorical brutality became a cathartic tool for motivating action and change. As Emory said, “You get to vent your frustration by identifying with the people in the drawings.” Least recognized are his works that show joy in communities, cultivating love and solidarity with people who want to create a just world. With bold images and strong liberation messages that echoed other freedom fights around the world, the Black Panther newspaper was an international and multicultural publication.

Emory explained that initially he tried to create woodcuts for his illustrations, but time restraints required faster methods, and he achieved a similar effect using his signature bold black ink and marker outlines. Collage was another essential technique that allowed him to combine photographs with drawing and text to amplify the paper’s editorial content and add more layers and depth to the artwork. He drew political cartoons and became notorious for his policeman-as-pig caricatures, the comparison first published by Francis Grose in 1811.4 Along with others in the alternative press and counter-culture movements, he helped embed “pigs” in the late 1960s and early 1970s verbal and visual language.

Around 2007, after a trip to Australia and learning from young people, he started using Photoshop to remix some of his earlier drawings and connect past work with the present. Working digitally allowed full use of color, patterns not available in black-and-white rubdown sheets during the BP days, and an opportunity to reflect on what had changed since he made the original drawing. His goal was to reinterpret the artworks’ messages in a more contemporary style and context.

In 2007, as the US was about to elect its first Black president and still struggled with the same issues that galvanized the BPP, a monograph of Emory’s work reached the mainstream art and design worlds. Retrospectives at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (2008) and the New Museum in New York City (2009) brought his work to new generations and audiences in a political environment between the Black Power movement and the emerging Black Lives Matter movement. He never retired from activism and responded to a steady stream of invitations to travel throughout the US and internationally, showing and speaking about his work. Emory also continued “manufacturing creativity,” often doing collaborative projects with artists and activists when he visited. He found solidarity and a sense of shared commitment with others who used, as he described, “resistance and self-determination” to deal with challenges in their lives and in their countries.

The COVID-19 virus curtailed his in-person travel, but he participated in even more frequent virtual events. People remain attracted to his persistent belief that each one can help create the world they want. In turn, others inspire him, especially young people, who provide the fuel to continue his manufacturing of art. His life and career prove that change does happen. His vision has not changed, but the world has. The long and diverse list of exhibition and lecture venues, honors and awards, along with the global hearts and minds he has touched, affirm that his work will continue to inspire people who want to understand his vision. Hope is at the core of his vision. At the end of every presentation, he raises his fist and says matter of factly, “All power to the people.”

Colette Gaiter

Professor, Department of Africana Studies,

Department of Art & Design, University of Delaware