When I interviewed Jack Potter for appointment to faculty at the School of Visual Arts, the interview turned bizarre. He didn’t speak to me and didn’t look at me. Then I realized he had just returned from teaching at Art Center College of Deign in California where he’d had a terrible fight with the director. There I was—at the time—with my title of director. I understood his clash of feelings, so I took him up to see the studio in which he would be holding his classes. He moved about sniffed the air, and said, “This smells right, the way a school studio should smell.”

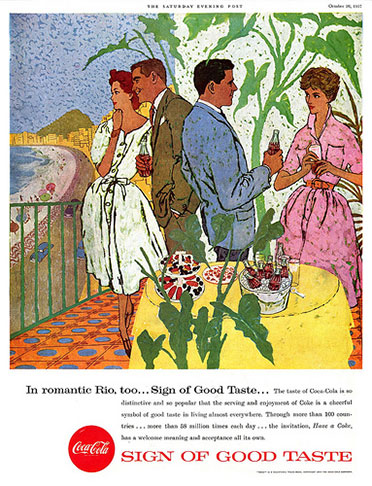

From there he went on to become the most popular Drawing teacher in New York City. At the same time his commercial work was a soaring success; it had appeared in the major women’s magazines and for national advertisers such as Coca-Cola and Northeast airlines. He stunned the work with his exquisite line and palette evocative of Bonnard. Everybody wanted Potter, including students who wanted to draw and illustrate like him.

Then he got sick and I had to put him in St. Vincent’s Hospital. I would visit and we would talk until finally one day he said “I’m not going to do commercial work anymore.” “Why?” I asked. “All they wanted me to do is the same thing over and over again. What I really want to do is teach.” I ignored the school regulation that all our teachers should be working professionals and immediately accepted his proposal, realizing what an exceptional teacher he was.

When he came out of the hospital, I had him go with me to Wednesday matinees on Broadway. He liked that. It helped him recover. The matinees were unusual. Not so much for the quality of the plays but for what the women did when the curtain came down. They stormed him for Autographs, thinking he was Yul Brynner. He handles it well, just waved them away.

But this time we gad become friends, not social friends, but business friends, and when the school moved from Second Avenue to the middle of 23rd Street, he volunteered to paint the lobby—lilac. His assistant at the time was fourteen-year-old David Rhodes, who would late become the president of SVA.

Now, Jack was never easy on the Department Chairs. He refused to go to their meetings or participate in their exhibitions. However, any school that hopes to be great should be able to handle the egocentricities of their great teachers. Each year, I’d get a letter of complaint from a student—some middle-aged executive not used to taking criticism. I would reply: “One should be honored to study with Maestro Potter. Just hang in there and in the end, you’ll appreciate him.” True enough, at the end of the semester I would get a letter saying “You were right and I’m going to re-enroll.”

For more than forty years Potter gave a bravura performance teaching that classical member of the triad of the Renaissance curriculum: drawing. It took courage to move against the tide when many schools were quietly dropping drawing from their curriculum He persevered, along with some few others, in the face of the tyranny of the times, when there was less and less interest in the words beauty and line.

His course “Drawing and Thinking” became legendary. Numbered along the alumni in Room 501 were beginning and advanced students, mature artists in flight from the dominance of galleries, curators, and art dealers. All of them “from recollection in tranquility,” could attest to his passion for what he taught, the imagination that he brought to his famous premises, and the rigor of his discipline that his students soon self-imposed. Among Jack Potter’s many talents was an ability to persuade students to change their ways of thinking and consequently, their way of drawing.

Most administrators say that you will be missed. We’ll go in one better: you’ll not see his like again.

Silas H. Rhodes

Chairman and founder of the School of Visual Arts