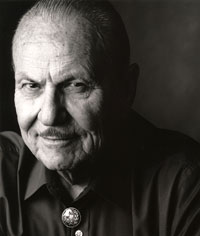

(1911-1996) I doubt that Burne Hogarth ever envisioned his modest row of drawing instruction bricks would serve as foundation for one of the most formidable commercial art institutions ever assembled. Hogarth maintained his focus on the human figure, or, more specifically, the dynamic qualities of anatomy in motion, which he believed to be at the core of all representational art.

While his personal instruction served as the prime attraction at the beginning, the growth of this intimate academy began to expand. He wisely stepped back and allowed a faculty of professionals in related fields to expand the syllabus and watched his Cartoonist and Illustrator School transform into the School of Visual Arts.

At coffee klatches that often followed his classes, Hogarth’s students enjoyed the intellectual exchanges with this expert on art history (as well as almost any other subject that came up). After my gag remark, “Don’t ask Burne Hogarth about the weather or the time unless you want to get an earful on Galileo,” somehow got back to him, he said to me with a smile, “Copernicus might have been a better choice.” And just when you thought you had him with a bit of art trivia, he’d counter with, “Well, I’m afraid Masaccio did that long before Tintoretto.”

When I jokingly accused him of making up artists as he did muscles that didn’t exist on any human form, he insisted “those muscles actually did exist but few of us ever see them in that advanced stage of development.” “Then I guess it’s okay for me not to include them in a drawing of boring old muscle-minus Henry Hinglehoffer — and not Tarzan — mailing a letter.” I quickly assumed an exaggerated pose ala a typical Hogarth figure. Not missing a beat, he quickly proceeded to draw a loin-clothed clad, bulging muscled image of boring old Henry Hinglehoffer in a very exaggerated “mailing a letter” pose. I immediately captioned the drawing, “The Mail Figure in Motion.” He was delighted.

The brilliant demonstration drawings Hogarth made for his classes became the basis for his successful line of art instruction books, reaching an appreciative audience. He enjoyed the celebrity that earned him a worldwide reputation, especially in France where his work was honored and permanently enshrined in major museums.

Words by Nick Meglin

Former editor of Mad Magazine